![ohara[6] ohara[6]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgm5VN5ctYo9joPQST2ZpU1Rn4OrXeiTJLcxMFXyuREcO2sb4Tl-2BOU78EnrcyJJhchGXUgI0pzkHtuaVdve9TTfkNa8fIpgfanyMpUCSkMFR91KiPtxPQi5_2ixvOMUaB6Fksz0HYPPav/?imgmax=800)

"Hike/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture" Through February 13, 2001. National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C.

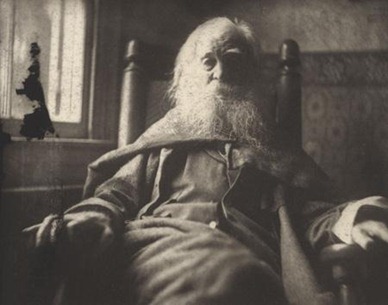

“Hide/Seek” begins its American story, as is appropriate, with Walt Whitman. Walt was, after all, the great bard of American self-invention. If there was a new identity to be tried, Walt was ready to sing its praises. It has been speculated that Whitman had a more than passing interest in homosexuality. The manuscript version of his poem “Once I Pass'd Through A Populous City” contains the following lines:

Day by day and night by night we were together — all else has long been forgotten by me,

I remember I saw only that man who passionately clung to me,

Again we wander, we love, we separate again,

Again he holds me by the hand, I must not go,

I see him close beside me with silent lips sad and tremulous.

It is never clear in Whitman exactly how much he is attracted to men as men, and how much he is simply attracted to everyone and everything. Whitman’s sexuality is so overflowing as to be beyond any specific identity. One gets the feeling that Whitman got the same amount of erotic charge rubbing up against things in his kitchen as he did getting close to human beings. That is part of his overall metaphysics of joy and abundance.

Up through the early part of the 20th century, the Whitman approach to sexuality provided something of a safe haven for homosexuality. When everyone is being natural and happy and naïve, there is less need to ask specific questions. A painting in the show, “River Front No. 1” by George Wesley Bellows (1915), captures this attitude well. A bunch of guys are hanging out on the riverfront. There are all kinds of guys. Some of them have their clothes off, some don’t. There is a vague hedonism to the scene, but it is hard to place. It is not a gay scene exactly, or is it?

But it was this Whitmanesque fluidity and openness that had to be abandoned for a truly specific gay identity to emerge. Questions had to asked, identities had to be sorted out. There was a feeling, even maybe among gays themselves, that the ambiguity of the Whitman approach still glossed over a lie. A grand polymorphous panamorism might be nice as a poetic fantasy, but it did not address the problems faced by those who found themselves attracted to and falling in love with members of their own sex.

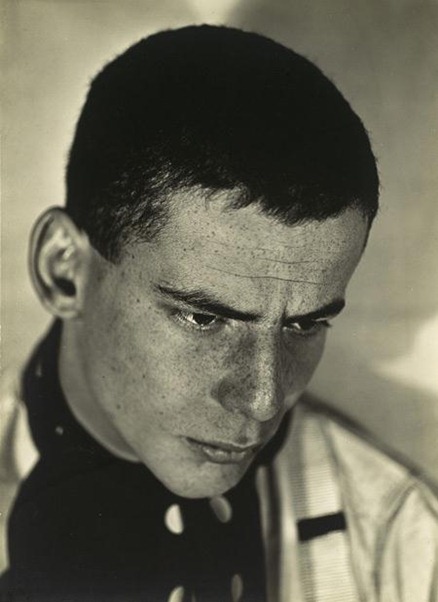

The Whitman ambiguity, however, lingered on into the period between the two World Wars. A 1930 photo of Lincoln Kirstein by Walker Evans for example, is a beautiful shot of a brooding young man. Is it also about being gay? We are not sure. The participants aren’t sure. There is no category, yet, through which that specific identity can find its voice.

No comments:

Post a Comment